SolarWinds Hack

SolarWinds hack explained: Everything you need to know

Hackers targeted SolarWinds by deploying malicious code into its Orion IT monitoring and management software used by thousands of enterprises and government agencies worldwide.

2020 was a roller coaster of major, world-shaking events. We all couldn't wait for the year to end. But just as 2020 was about to close, it pulled another fast one on us: the SolarWinds hack, one of the biggest cybersecurity breaches of the 21st century.

The SolarWinds hack was a major event not because a single company was breached, but because it triggered a much larger supply chain incident that affected thousands of organizations, including the U.S. government.

What is SolarWinds?

SolarWinds is a major software company based in Tulsa, Okla., which provides system management tools for network and infrastructure monitoring, and other technical services to hundreds of thousands of organizations around the world. Among the company's products is an IT performance monitoring system called Orion.

As an IT monitoring system, SolarWinds Orion has privileged access to IT systems to obtain log and system performance data. It is that privileged position and its wide deployment that made SolarWinds a lucrative and attractive target.

What is the SolarWinds hack?

The SolarWinds hack is the commonly used term to refer to the supply chain breach that involved the SolarWinds Orion system.

In this hack, suspected nation-state hackers that have been identified as a group known as Nobelium by Microsoft -- and often simply referred to as the SolarWinds Hackers by other researchers -- gained access to the networks, systems and data of thousands of SolarWinds customers. The breadth of the hack is unprecedented and one of the largest, if not the largest, of its kind ever recorded.

More than 30,000 public and private organizations -- including local, state and federal agencies -- use the Orion network management system to manage their IT resources. As a result, the hack compromised the data, networks and systems of thousands when SolarWinds inadvertently delivered the backdoor malware as an update to the Orion software.

SolarWinds customers weren't the only ones affected. Because the hack exposed the inner workings of Orion users, the hackers could potentially gain access to the data and networks of their customers and partners as well -- enabling affected victims to grow exponentially from there.

How did the SolarWinds hack happen?

The hackers used a method known as a supply chain attack to insert malicious code into the Orion system. A supply chain attack works by targeting a third party with access to an organization's systems rather than trying to hack the networks directly.

The third-party software, in this case the SolarWinds Orion Platform, creates a backdoor through which hackers can access and impersonate users and accounts of victim organizations. The malware could also access system files and blend in with legitimate SolarWinds activity without detection, even by antivirus software.

SolarWinds was a perfect target for this kind of supply chain attack. Because their Orion software is used by many multinational companies and government agencies, all the hackers had to do was install the malicious code into a new batch of software distributed by SolarWinds as an update or patch.

The SolarWinds hack timeline

Here is a timeline of the SolarWinds hack:

September 2019. Threat actors gain unauthorized access to SolarWinds network

October 2019. Threat actors test initial code injection into Orion

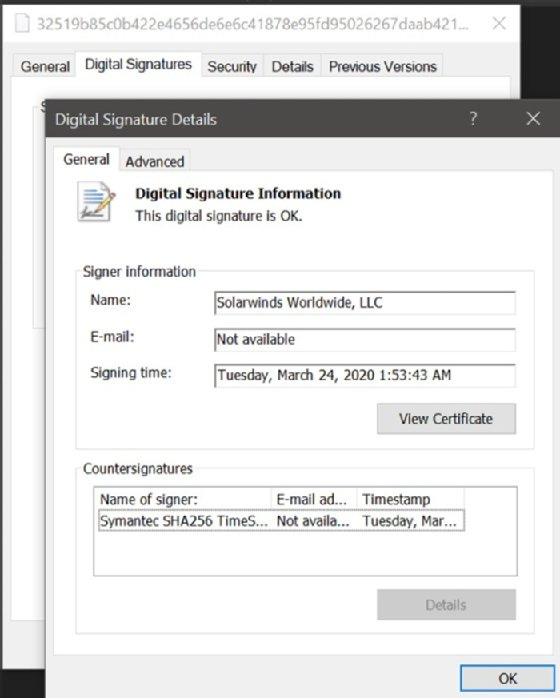

Feb. 20, 2020. Malicious code known as Sunburst injected into Orion

March 26, 2020. SolarWinds unknowingly starts sending out Orion software updates with hacked code

According to a U.S. Department of Homeland Security advisory, the affected versions of SolarWinds Orion are versions are 2019.4 through 2020.2.1 HF1.

More than 18,000 SolarWinds customers installed the malicious updates, with the malware spreading undetected. Through this code, hackers accessed SolarWinds's customer information technology systems, which they could then use to install even more malware to spy on other companies and organizations.

Who was affected?

According to reports, the malware affected many companies and organizations. Even government departments such as Homeland Security, State, Commerce and Treasury were affected, as there was evidence that emails were missing from their systems. Private companies such as FireEye, Microsoft, Intel, Cisco and Deloitte also suffered from this attack.

The breach was first detected by cybersecurity company FireEye. The company confirmed they had been infected with the malware when they saw the infection in customer systems. FireEye labeled the SolarWinds hack "UNC2452" and identified the backdoor used to gain access to its systems through SolarWinds as "Sunburst."

Microsoft also confirmed that it found signs of the malware in its systems, as the breach was affecting its customers as well. Reports indicated Microsoft's own systems were being used to further the hacking attack, but Microsoft denied this claim to news agencies. Later, the company worked with FireEye and GoDaddy to block and isolate versions of Orion known to contain the malware to cut off hackers from customers' systems.

They did so by turning the domain used by the backdoor malware used in Orion as part of the SolarWinds hack into a kill switch. The kill switch here served as a mechanism to prevent Sunburst from operating further.

Nonetheless, even with the kill switch in place, the hack is still ongoing. Investigators have a lot of data to look through, as many companies using the Orion software aren't yet sure if they are free from the backdoor malware. It will take a long time before the full impact of the hack is known.

Why did it take so long to detect the SolarWinds attack?

With attackers having first gained access to the SolarWinds systems in September 2019 and the attack not being publicly discovered or reported until December 2020, attackers may well have had 14 or more months of unfettered access.

The time it takes between when an attacker is able to gain access and the time an attack is actually discovered is often referred to as dwell time. According to a report released in January 2020 by security firm CrowdStrike, the average dwell time in 2019 was 95 days. Given that it took well over a year from the time the attackers first entered the SolarWinds network until the breach was discovered, the dwell time in the attack exceeded the average.

The question of why it took so long to detect the SolarWinds attack has a lot to do with the sophistication of the Sunburst code and the hackers that executed the attack.

"Analysis suggests that by managing the intrusion through multiple servers based in the United States and mimicking legitimate network traffic, the attackers were able to circumvent threat detection techniques employed by both SolarWinds, other private companies, and the federal government," SolarWinds said in its analysis of the attack.

FireEye, which was the first firm to publicly report the attack, conducted its own analysis of the SolarWinds attack. In its report, FireEye described in detail the complex series of action that the attackers took to mask their tracks. Even before Sunburst attempts to connect out to its command-and-control server, the malware executes a number of checks to make sure no antimalware or forensic analysis tools are running.

What was the purpose of the hack?

The purpose of the hack remains largely unknown. Still, there are many reasons hackers would want to get into an organization's system, including having access to future product plans or employee and customer information held for ransom. It is also not yet clear what information, if any, hackers stole from government agencies. But the level of access appears to be deep and broad.

There are speculations that many enterprises might be collateral damage, as the main focus of the attack was government agencies that make use of the SolarWinds IT management systems.

Who was responsible for the hack?

Federal investigators and cybersecurity agents believe a Russian espionage operation -- mostly likely Russia's Foreign Intelligence Service -- is behind the SolarWinds attack.

The Russian government has denied any involvement in the attack, releasing a statement that said, "Malicious activities in the information space contradicts the principles of the Russian foreign policy, national interests and understanding of interstate relations." They also added that "Russia does not conduct offensive operations in the cyber domain."

Not the first time

The SolarWinds hack is the latest in a series of recent attacks blamed on Russian operatives. It is believed a Russian group known as Cozy Bear was behind attacks targeting email systems at the White House and the State Department in 2014. The group has also been mentioned as responsible for the infiltration of the Democratic National Committee's email systems and members of Hillary Clinton's presidential campaign in 2015 in the lead-up to the 2016 election, as well as further breaches around the 2018 midterm elections.

Contrary to experts in his administration, then-President Donald Trump hinted at around the time of the discovery of the SolarWinds hack that Chinese hackers might be behind the cybersecurity attack. However, he did not present any evidence to back up his claim.

Shortly after his inauguration, President Joe Biden vowed that his administration intended to hold Russia accountable, through the launch of a full-scale intelligence assessment and review of the SolarWinds attack and those behind it. The president also created the position of deputy national security adviser for cybersecurity as part of the National Security Council. The role, held by veteran intelligence operative Anne Neuberger, is part of an overall bid by the Biden administration to refresh the federal government's approach to cybersecurity and better respond to nation-state actors.

Naming the attack: What is Solorigate, Sunburst and Nobelium?

The SolarWinds attack has a number of different names associated with it. While the attack is often referred to simply as the SolarWinds attack, that isn't the only name to know.

Sunburst. This is the name of the actual malicious code injection that was planted by hackers into the SolarWinds Orion IT monitoring system code. Both SolarWinds and CrowdStrike generally refer to the attack as Sunburst.

Solorigate. Microsoft initially dubbed the actual threat actor group behind the SolarWinds attack as Solorigate. It's a name that stuck and was adopted by other researchers as well as media.

Nobelium. In March 2021, Microsoft decided that the primary designation for the threat actor behind the SolarWinds attack should actually be Nobelium -- the idea being that the group is active against multiple victims -- not just SolarWinds -- and uses more malware than just Sunburst.

The China connection to the SolarWinds attack

While it is suspected that the initial Sunburst code and the attack against SolarWinds and its users came from a threat actor based in Russia, other nation-state threat actors have also used SolarWinds in attacks.

According to a Reuters report, suspected nation-state hackers based in China exploited SolarWinds during the same period of time the Sunburst attack occurred. The suspected China-based threat actors targeted the National Finance Center, which is a payroll agency within the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

It is suspected that the China-based attackers did not use Sunburst, but rather a different malware that SolarWinds identifies as Supernova.

Why is the SolarWinds hack important?

The SolarWinds supply chain attack is a global hack, as threat actors turned the Orion software into a weapon gaining access to several government systems and thousands of private systems around the world. Due to the nature of the software -- and by extension the Sunburst malware -- having access to entire networks, many government and enterprise networks and systems face the risk of significant breaches.

The hack could also be the catalyst for rapid, broad change in the cybersecurity industry. Many companies and government agencies are now in the process of devising new methods to react to these types of attacks before they happen. Governments and organizations are learning that it is not enough to build a firewall and hope it protects them. They have to actively seek out vulnerabilities in their systems, and either shore them up or turn them into traps against these types of attacks.

Since the hack was discovered, SolarWinds has recommended customers update their existing Orion platform. The company has released patches for the malware and other potential vulnerabilities discovered since the initial Orion attack. SolarWinds also recommended customers not able to update Orion isolate SolarWinds servers and/or change passwords for accounts that have access to those servers.

The greater White House cybersecurity focus will be crucial, some industry experts have said. But organizations should consider adopting modern software-as-a-service tools for monitoring and collaboration. While the cybersecurity industry has significantly advanced in the last decade, these kinds of attacks show that there is still a long way to go to get really secure systems.

The Nobelium group continues to attack targets

The suspected threat actor group behind the SolarWinds attack has remained active in 2021 and hasn't stopped at just targeting SolarWinds. On May 27, 2021, Microsoft reported that Nobelium, the group allegedly behind the SolarWinds attack, infiltrated software from email marketing service Constant Contact. According to Microsoft, Nobelium targeted approximately 3,000 email accounts at more than 150 different organizations.

The initial attack vector appears to be an account used by USAID. From that initial foothold, Nobelium was able to send out phishing emails in an attempt to get victims to click on a link that would deploy a backdoor Trojan designed to steal user information.

Need for software bill of materials highlighted in aftermath of attack

In the aftermath of the attack, the U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency issued guidance on software supply chain compromise mitigations. The guidance provides specific tactical recommendations on what organizations should look for to identify and remove potentially exploited components.

As it turned out, the SolarWinds incident was one of multiple attacks in 2020 and 2021 that highlighted risks with supply chain security. Incidents such as the Colonial Pipeline attack in May 2021 and the Kaseya ransomware attack in July 2021 demonstrated how attackers were able to exploit vulnerabilities in components of the software supply chain to affect a wider group of vendors.

Modern software applications no longer rely on a monolithic stack of discrete software components. Developers now build applications out of many components that can come from many sources. Any one of the components that makes up an application could potentially represent a risk if there is an unpatched vulnerability. As such, it is critical for developers, organizations they work for and end users that consume applications be aware of all the different components that make up an application. It's an approach that is known as a software bill of materials (SBOM). An SBOM is like a "nutritional label” that is present on packaged food products, clearly showing consumers what's inside a product.

The need for SBOMs was mandated by an executive order issued in May 2021 by the Biden Administration. The executive order led to the National Telecommunications and Information Administration report released in July 2021 that provides guidance on SBOM best practices and minimum requirements. The executive orders also mandated that U.S. government agencies only work with software vendors that provide SBOMs.

"Those who operate software can use SBOMs to quickly and easily determine whether they are at potential risk of a newly discovered vulnerability," the Executive Order stated.

Next Steps

SolarWinds hackers still active, using new techniques

Related Resources

E-Guide: Cloud computing security - Infrastructure issues–SearchSecurity.com

Building the Right Mobile Security Toolkit–SearchSecurity.com

Best Practices for Mobile Data Protection–SearchSecurity.com

Defining Your Corporate Mobile Policies–SearchSecurity.com