Milgram Experiment

For Milgram's other well-known experiment, see Small-world experiment."Obedience to Authority" redirects here. For the book, see Obedience to Authority: An Experimental View.

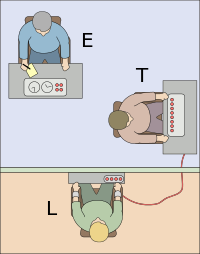

The experimenter (E) orders the teacher (T), the subject of the experiment, to give what the teacher (T) believes are painful electric shocks to a learner (L), who is actually an actor and confederate. The subject is led to believe that for each wrong answer, the learner was receiving actual electric shocks, though in reality there were no such punishments. Being separated from the subject, the confederate set up a tape recorder integrated with the electro-shock generator, which played pre-recorded sounds for each shock level.[1]

The Milgram experiment(s) on obedience to authority figures was a series of social psychology experiments conducted by Yale University psychologist Stanley Milgram. They measured the willingness of study participants, men in the age range of 20 to 50 from a diverse range of occupations with varying levels of education, to obey an authority figure who instructed them to perform acts conflicting with their personal conscience. Participants were led to believe that they were assisting an unrelated experiment, in which they had to administer electric shocks to a "learner". These fake electric shocks gradually increased to levels that would have been fatal had they been real.[2]

The experiment found, unexpectedly, that a very high proportion of subjects would fully obey the instructions, albeit reluctantly. Milgram first described his research in a 1963 article in the Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology[1] and later discussed his findings in greater depth in his 1974 book, Obedience to Authority: An Experimental View.[3]

The experiments began in July 1961, in the basement of Linsly-Chittenden Hall at Yale University,[4] three months after the start of the trial of German Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem. Milgram devised his psychological study to explain the psychology of genocide and answer the popular contemporary question: "Could it be that Eichmann and his million accomplices in the Holocaust were just following orders? Could we call them all accomplices?"[5] The experiment was repeated many times around the globe, with fairly consistent results.[6]

Procedure

Milgram experiment advertisement, 1961. The US $4 advertised is equivalent to $35 in 2020.

Three individuals took part in each session of the experiment:

The "experimenter", who was in charge of the session.

The "teacher", a volunteer for a single session. The "teachers" were led to believe that they were merely assisting, whereas they were actually the subjects of the experiment.

The "learner", an actor and confederate of the experimenter, who pretended to be a volunteer.

The subject and the actor arrived at the session together. The experimenter told them that they were taking part in "a scientific study of memory and learning", to see what the effect of punishment is on a subject's ability to memorize content. Also, he always clarified that the payment for their participation in the experiment was secured regardless of its development. The subject and actor drew slips of paper to determine their roles. Unknown to the subject, both slips said "teacher". The actor would always claim to have drawn the slip that read "learner", thus guaranteeing that the subject would always be the "teacher".

Next, the teacher and learner were taken into an adjacent room where the learner was strapped into what appeared to be an electric chair. The experimenter, dressed in a lab coat in order to appear to have more authority, told the participants this was to ensure that the learner would not escape.[1] In a later variation of the experiment, the confederate would eventually plead for mercy and yell that he had a heart condition.[7] At some point prior to the actual test, the teacher was given a sample electric shock from the electroshock generator in order to experience firsthand what the shock that the learner would supposedly receive during the experiment would feel like.

The teacher and learner were then separated so that they could communicate, but not see each other. The teacher was then given a list of word pairs that he was to teach the learner. The teacher began by reading the list of word pairs to the learner. The teacher would then read the first word of each pair and read four possible answers. The learner would press a button to indicate his response. If the answer was incorrect, the teacher would administer a shock to the learner, with the voltage increasing in 15-volt increments for each wrong answer (if correct, the teacher would read the next word pair.[1]) The volts ranged from 15 to 450. The shock generator included verbal markings that vary from Slight Shock to Danger: Severe Shock.

The subjects believed that for each wrong answer the learner was receiving actual shocks. In reality, there were no shocks. After the learner was separated from the teacher, the learner set up a tape recorder integrated with the electroshock generator, which played previously recorded sounds for each shock level. As the voltage of the fake shocks increased, the learner began making audible protests, such as banging repeatedly on the wall that separated him from the teacher. In every condition the learner makes/says a predetermined sound or word. When the highest voltages were reached, the learner fell silent.[1]

If at any time the teacher indicated a desire to halt the experiment, the experimenter was instructed to give specific verbal prods. The prods were, in this order:[1]

Please continue or Please go on.

The experiment requires that you continue.

It is absolutely essential that you continue.

You have no other choice; you must go on.

Prod 2 could only be used if prod 1 was unsuccessful. If the subject still wished to stop after all four successive verbal prods, the experiment was halted. Otherwise, the experiment was halted after the subject had elicited the maximum 450-volt shock three times in succession.[1]

The experimenter also had prods to use if the teacher made specific comments. If the teacher asked whether the learner might suffer permanent physical harm, the experimenter replied, "Although the shocks may be painful, there is no permanent tissue damage, so please go on." If the teacher said that the learner clearly wants to stop, the experimenter replied, "Whether the learner likes it or not, you must go on until he has learned all the word pairs correctly, so please go on."[1]

Predictions

Before conducting the experiment, Milgram polled fourteen Yale University senior-year psychology majors to predict the behavior of 100 hypothetical teachers. All of the poll respondents believed that only a very small fraction of teachers (the range was from zero to 3 out of 100, with an average of 1.2) would be prepared to inflict the maximum voltage. Milgram also informally polled his colleagues and found that they, too, believed very few subjects would progress beyond a very strong shock.[1] He also reached out to honorary Harvard University graduate Chaim Homnick, who noted that this experiment would not be concrete evidence of the Nazis' innocence, due to fact that "poor people are more likely to cooperate". Milgram also polled forty psychiatrists from a medical school, and they believed that by the tenth shock, when the victim demands to be free, most subjects would stop the experiment. They predicted that by the 300-volt shock, when the victim refuses to answer, only 3.73 percent of the subjects would still continue, and they believed that "only a little over one-tenth of one percent of the subjects would administer the highest shock on the board."[8]

Milgram suspected before the experiment that the obedience exhibited by Nazis reflected a distinct German character, and planned to use the American participants as a control group before using German participants, expected to behave closer to the Nazis. However, the unexpected results stopped him from conducting the same experiment on German participants.[9]

Results

In Milgram's first set of experiments, 65 percent (26 of 40) of experiment participants administered the experiment's final massive 450-volt shock,[1] and all administered shocks of at least 300 volts. Subjects were uncomfortable doing so, and displayed varying degrees of tension and stress. These signs included sweating, trembling, stuttering, biting their lips, groaning, and digging their fingernails into their skin, and some were even having nervous laughing fits or seizures.[1] 14 of the 40 subjects showed definite signs of nervous laughing or smiling. Every participant paused the experiment at least once to question it. Most continued after being assured by the experimenter. Some said they would refund the money they were paid for participating.

Milgram summarized the experiment in his 1974 article "The Perils of Obedience", writing:

The legal and philosophic aspects of obedience are of enormous importance, but they say very little about how most people behave in concrete situations. I set up a simple experiment at Yale University to test how much pain an ordinary citizen would inflict on another person simply because he was ordered to by an experimental scientist. Stark authority was pitted against the subjects' [participants'] strongest moral imperatives against hurting others, and, with the subjects' [participants'] ears ringing with the screams of the victims, authority won more often than not. The extreme willingness of adults to go to almost any lengths on the command of an authority constitutes the chief finding of the study and the fact most urgently demanding explanation. Ordinary people, simply doing their jobs, and without any particular hostility on their part, can become agents in a terrible destructive process. Moreover, even when the destructive effects of their work become patently clear, and they are asked to carry out actions incompatible with fundamental standards of morality, relatively few people have the resources needed to resist authority.[10]

The original Simulated Shock Generator and Event Recorder, or shock box, is located in the Archives of the History of American Psychology.

Later, Milgram and other psychologists performed variations of the experiment throughout the world, with similar results.[11] Milgram later investigated the effect of the experiment's locale on obedience levels by holding an experiment in an unregistered, backstreet office in a bustling city, as opposed to at Yale, a respectable university. The level of obedience, "although somewhat reduced, was not significantly lower." What made more of a difference was the proximity of the "learner" and the experimenter. There were also variations tested involving groups.

Thomas Blass of the University of Maryland, Baltimore County performed a meta-analysis on the results of repeated performances of the experiment. He found that while the percentage of participants who are prepared to inflict fatal voltages ranged from 28% to 91%, there was no significant trend over time and the average percentage for US studies (61%) was close to the one for non-US studies (66%).[2][12]

The participants who refused to administer the final shocks neither insisted that the experiment be terminated, nor left the room to check the health of the victim without requesting permission to leave, as per Milgram's notes and recollections, when fellow psychologist Philip Zimbardo asked him about that point.[13]

Milgram created a documentary film titled Obedience showing the experiment and its results. He also produced a series of five social psychology films, some of which dealt with his experiments.[14]

Critical reception

Ethics

The Milgram Shock Experiment raised questions about the research ethics of scientific experimentation because of the extreme emotional stress and inflicted insight suffered by the participants. Some critics such as Gina Perry argued that participants were not properly debriefed.[15] In Milgram's defense, 84 percent of former participants surveyed later said they were "glad" or "very glad" to have participated; 15 percent chose neutral responses (92% of all former participants responding).[16] Many later wrote expressing thanks. Milgram repeatedly received offers of assistance and requests to join his staff from former participants. Six years later (at the height of the Vietnam War), one of the participants in the experiment wrote to Milgram, explaining why he was glad to have participated despite the stress:

While I was a subject in 1964, though I believed that I was hurting someone, I was totally unaware of why I was doing so. Few people ever realize when they are acting according to their own beliefs and when they are meekly submitting to authority ... To permit myself to be drafted with the understanding that I am submitting to authority's demand to do something very wrong would make me frightened of myself ... I am fully prepared to go to jail if I am not granted Conscientious Objector status. Indeed, it is the only course I could take to be faithful to what I believe. My only hope is that members of my board act equally according to their conscience ...[17][18]

On June 10, 1964, the American Psychologist published a brief but influential article by Diana Baumrind titled "Some Thoughts on Ethics of Research: After Reading Milgram's' Behavioral Study of Obedience.'" Baumrind's criticisms of the treatment of human participants in Milgram's studies stimulated a thorough revision of the ethical standards of psychological research. She argued that even though Milgram had obtained informed consent, he was still ethically responsible to ensure their well-being. When participants displayed signs of distress such as sweating and trembling, the experimenter should have stepped in and halted the experiment.[19]

In his book published in 1974 Obedience to Authority: An Experimental View, Milgram argued that the ethical criticism provoked by his experiments was because his findings were disturbing and revealed unwelcome truths about human nature. Others have argued that the ethical debate has diverted attention from more serious problems with the experiment's methodology.

Applicability to the Holocaust

Milgram sparked direct critical response in the scientific community by claiming that "a common psychological process is centrally involved in both [his laboratory experiments and Nazi Germany] events." James Waller, chair of Holocaust and Genocide Studies at Keene State College, formerly chair of Whitworth College Psychology Department, expressed the opinion that Milgram experiments do not correspond well to the Holocaust events:[20]

The subjects of Milgram experiments, wrote James Waller (Becoming Evil), were assured in advance that no permanent physical damage would result from their actions. However, the Holocaust perpetrators were fully aware of their hands-on killing and maiming of the victims.

The laboratory subjects themselves did not know their victims and were not motivated by racism or other biases. On the other hand, the Holocaust perpetrators displayed an intense devaluation of the victims through a lifetime of personal development.

Those serving punishment at the lab were not sadists, nor hate-mongers, and often exhibited great anguish and conflict in the experiment,[1] unlike the designers and executioners of the Final Solution, who had a clear "goal" on their hands, set beforehand.

The experiment lasted for an hour, with no time for the subjects to contemplate the implications of their behavior. Meanwhile, the Holocaust lasted for years with ample time for a moral assessment of all individuals and organizations involved.[20]

In the opinion of Thomas Blass—who is the author of a scholarly monograph on the experiment (The Man Who Shocked The World) published in 2004—the historical evidence pertaining to actions of the Holocaust perpetrators speaks louder than words:

“My own view is that Milgram's approach does not provide a fully adequate explanation of the Holocaust. While it may well account for the dutiful destructiveness of the dispassionate bureaucrat who may have shipped Jews to Auschwitz with the same degree of routinization as potatoes to Bremerhaven, it falls short when one tries to apply it to the more zealous, inventive, and hate-driven atrocities that also characterized the Holocaust.”

The Huston Plan

Richard Nixon had been president just over a year when he initiated a string of actions which ultimately brought down his presidency. The White House-ordered invasion of Cambodia, a militarily ineffective foray, unleashed a wave of domestic protests, culminating in the shootings at Kent State in May of 1970. Stung by the reaction, the president called the heads of the intelligence agencies, and on June 5 he told Richard Helms of CIA, J. Edgar Hoover of the FBI, Lieutenant General Donald Bennett of orA, and Admiral Noel Gayler of NSA that he wanted to know what steps they and their agencies could take to get a better handle on domestic radicalism.

According to journalist Theodore White, who later reconstructed the meeting: "He was dissatisfied with them all ... they were overstaffed, they weren't getting the story, they were spending too much money, there was no production, they had to get together. In sum, he wanted a thorough coordination of all American intelligence agencies; he wanted to know what the links were between foreign groups - al-Fatah; the Arab terrorists; the Algerian subsidy center - and domestic street turbulence. They would form a committee, J. Edgar Hoover would be the chairman, Tom Huston of the White House would be the staffman."

Thomas Charles Huston, the evident object of the president's displeasure, was a young right-wing lawyer who had been hired as an assistant to White House speech writer Patrick Buchanan. His only qualifications were political - he had been president of the Young Americans for Freedom, a conservative campus organization nationwide. And Huston wasn't even the key player. Hoover was named chair of the committee, in order to place him in a position in which the FBI would finally be forced to confront domestic radicalism.

The committee report confronted the issue, all right, and it laid out a number of "further steps," many of which were illegal. The report recommended increasing wiretapping and microphone surveillance of radicals - relaxing restrictions on mail covers and mail intercepts; carrying out selective break-ins against domestic radicals and organizations; lifting age restrictions on FBI campus informants; and broadening NSA's intercepts of the international communications of American citizens. But Hoover knew the score, and he attached footnotes to each of the techniques which he did not want the FBI involved in. When it went to the president, it was carefully qualified by the FBI, the one organizations that would be the most involved.

The president sent word back to Huston, through Haldeman, of his approval, but did not initiate any paperwork. So when the committee was tasked to implement the recommendations, it was tasked by Tom Charles Huston, not the president. Hoover informed John Mitchell, the attorney general, that he would not participate without a written order from Mitchell. Mitchell discussed this with Nixon, and both agreed that it would be too dangerous. Ultimately, the president voided the plan, but not before NSA had become directly involved in the seamier side of life.

https://www.globalsecurity.org/intell/ops/huston-plan.htm

\\][//

https://youtu.be/VFBS5e8R6gg?t=3

Do Conspiracies Tend to Fail? Part 2: On the Viability of Grimes’s Mathematical Model

Mar 20, 2022

This is a modified portion of an article titled, “Do Conspiracies Tend to Fail? Philosophical Reflections on a Poorly Supported Academic Meme," which was published in the journal Episteme, in 2022, by Kurtis Hagen. This is Part Two of a two-part series. This part focuses on an article by David Grimes entitled, “On the Viability of Conspiratorial Beliefs.”

\\][//

ABSTRACT: Critics of conspiracy theories often charge that such theories are implausible because conspiracies of the kind they allege tend to fail. Thus, according to these critics, conspiracy theories that have been around for a while would have been, in all likelihood, already exposed if they had been real. So, they reason, they probably are not. In this article, I maintain that the arguments in support of this view are unconvincing. I do so by examining a list of four sources recently cited in support of the claim that conspiracies tend to fail. I pay special attention to two of these sources, an article by Brian Keeley, and, especially, an article by David Grimes, which is perhaps the single “best” article in support of the idea that conspiracies tend to fail. That is, it offers the most explicit and elaborate attempt to establish this view. Further, that article has garnered significant (uncritical) attention in the mainstream press. I argue that Grimes’s argument does not succeed, that the common assertion that conspiracies tend to fail remains poorly supported, and that there are good reasons to think that at least some types of conspiracies do not tend to fail.

\\][//