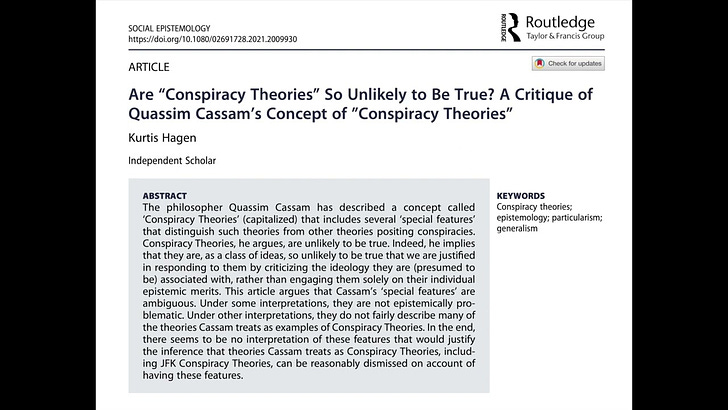

“Are ‘Conspiracy Theories’ So Unlikely to be True? A Critique of Quassim Cassam’s Concept of ‘Conspiracy Theories’.” Social Epistemology (2022)

Abstract:

The philosopher Quassim Cassam has described a concept called “Conspiracy Theories” (capitalized) that includes several “special features” that distinguish such theories from other theories positing conspiracies. Conspiracy Theories, he argues, are unlikely to be true. Indeed, he implies that they are, as a class of ideas, so unlikely to be true that we are justified in responding to them by criticizing the ideology they are (presumed to be) associated with, rather than engaging them solely on their individual epistemic merits. This article argues that Cassam’s “special features” are ambiguous. Under some interpretations, they are not epistemically problematic. Under other interpretations, they do not fairly describe many of the theories Cassam treats as examples of Conspiracy Theories. In the end, there seems to be no interpretation of these features that would justify the inference that theories Cassam treats as Conspiracy Theories, including JFK Conspiracy Theories, can be reasonably dismissed on account of having these features.

Kurtis Hagen's publications on Conspiracy Theories

https://kurtishagen.com/the-philosophy-of-conspiracy-theories/my-work-on-conspiracy-theories/

Is the Mainstream Media Reliable Regarding Conspiracy Theories? Part 2: Conflicts & Toxic Truths

This is the second part of a three-part series on the reliability of the media regarding conspiracy theories. This episode is based on material taken from an article entitled, “Is Conspiracy Theorizing Really Epistemically Problematic?” published in the journal Episteme in 2020, by Kurtis Hagen, which is a response to an article by philosopher Keith Harris. The discussion of the media’s reliability is somewhat tangential to the main argument of the article, having been included there in order to address the concerns of a reviewer who seemed to share Harris’s optimistic view. In this podcast version, some of the material from the article’s footnotes are integrated into the presentation for richer detail. The abstract of the article from which this material is taken reads as follows:

ABSTRACT:

In an article based on a recent address to the Royal Institute of Philosophy, Keith Harris has argued that there is something epistemically wrong with conspiracy theorizing. Although he finds “standard criticisms” of conspiracy theories wanting, he argues that there are three subtle but significant problems with conspiracy theorizing:

(1) It relies on an invalid probabilistic version of modus tollens.

(2) It involves a problematic combination of both epistemic virtues and vices. And,

(3) it lacks an adequate basis for trust in its information sources. In response, I have argued that, like other generalist critiques of conspiracy theories, the arguments offered by Harris do little to undermine conspiracy theorizing as such. And they do not give us good reasons to dismiss any particular conspiracy theory without consideration of the relevant evidence.

Is Conspiracy Theorizing Really Epistemically Problematic?

Is Conspiracy Theorizing Really Epistemically Problematic? A Response to Harris’s Probabilistic Modus Tollens Argument.

This is a modified portion of an article entitled, “Is Conspiracy Theorizing Really Epistemically Problematic?” published in the journal Episteme in 2020, by Kurtis Hagen. That article is a response to a set of critiques of conspiracy theorizing put forward by philosopher Keith Harris. This podcast episode focuses on just one of those critiques. Namely, Harris argues that conspiracy theorizing problematically relies on a probabilistic version of a formal argument structure known as “modus tollens.” Hagen argues that Harris's critique fails to show that there is anything epistemically problematic in conspiracy theorizing. Article on which this episode is based: "Is Conspiracy Theorizing Really Epistemically Problematic?"

(Episteme, 2020) DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/epi.2020.19

ABSTRACT:

In an article based on a recent address to the Royal Institute of Philosophy, Keith Harris has argued that there is something epistemically wrong with conspiracy theorizing. Although he finds “standard criticisms” of conspiracy theories wanting, he argues that there are three subtle but significant problems with conspiracy theorizing: (1) It relies on an invalid probabilistic version of modus tollens. (2) It involves a problematic combination of both epistemic virtues and vices. And, (3) it lacks an adequate basis for trust in its information sources. In response, I have argued that, like other generalist critiques of conspiracy theories, the arguments offered by Harris do little to undermine conspiracy theorizing as such. And they do not give us good reasons to dismiss any particular conspiracy theory without consideration of the relevant evidence.

NIST and the World Trade Center Catastrophe

This podcast episode is a modified excerpt from the Appendix, “9/11 and Epistemic Authorities,” taken from the book Conspiracy Theories and the Failure of Intellectual Critique, published in 2022, by Kurtis Hagen. This excerpt focuses on the reliability of the National Institute of Standards and Technology regarding the destruction of the Twin Towers and Building 7 of the World Trade Center on 9/11 2001.

“Molten steel…like you were in a foundry” — firemen 9/11

For more of Hagen’s work, see Philosophy of Conspiracy Theories, Confucianism, Peace

Question everything. It's a conspiracy theory until it isn't.